AI Is About Optimizing Success, But Not About Truth or Reality

“There Is No Success Like Failure,” Bob Dylan

Michael Dwyer/AP Photo

Recently, my ten-year-old grandson said out of nowhere, “Mistakes are more important than getting something right.” I was startled because I knew he hadn’t read this idea by the way he said it while climbing around on the back of the couch, with pieces of the jigsaw puzzle we were working on scattered on the seat. “How do you know that?” I asked. “I figured it out because it’s true. You learn from mistakes, but you don’t learn from what you get right. After you get something right, it’s just over, but you go on learning from your mistakes.” I felt really proud of him. I didn’t know that a ten-year-old could see this insight so clearly. Many adults don’t grasp the importance of learning from their mistakes.

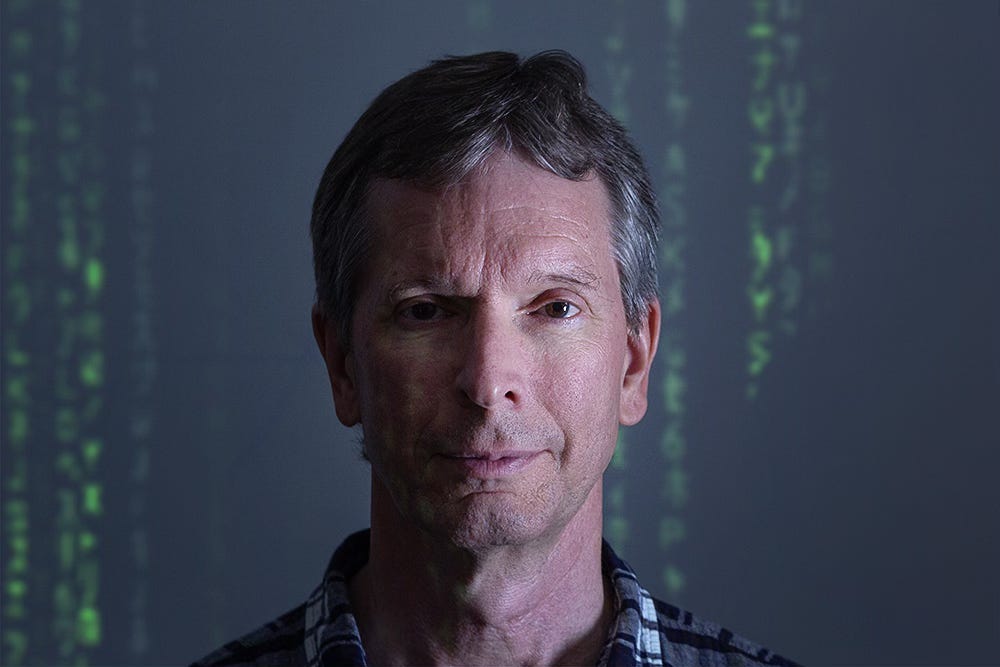

My grandson was thinking about truth, not simply what works or success. In a similar way, the cognitive scientist Donald Hoffman PhD who has advanced a powerful theory about the differences between truth and success refers to “what you get right” as “survival fitness.” Especially as laid out in his book The Case Against Reality: How Evolution Hid the Truth from Our Eyes, Hoffman argues that what humans perceive is shaped more by what helped us survive and reproduce than by what reflects reality accurately.

Hoffman uses the metaphor of the icon on a computer desktop: we learn to click on the icon to get something that helps us function, but we don’t know learn the circuity and code of the icon. We know what it looks like and we use it, but we don’t know what it is. Similarly, Hoffman claims that evolution has shaped us to survive, but not to see the truth. In my grandson’s words, we don’t learn from our mistakes as much as we optimize what we believe is “right.” And yet, as humans, we also have self-awareness and we can reflect on our mistakes even when we are not rewarded. (If this is puzzling, listen to the two podcasts linked here: they are with me and Michael Berger talking with Donald Hoffman on “Waking Up Is Not Enough: Flourishing in the Human Space.”)

Learn from Defeat and Failure

At the Center for Real Dialogue (www.realdialogue.org), one of our four principles is “Learn from defeat and failure.” We teach this principle not only because it’s helpful in life, but also because our approach to dialogue is based on “humanizing” our differences and acknowledging our subjectivity, as well as our individual ways of seeing and hearing.

One distinct feature of being human is that we all know we will die. Learning from our failures prepares us to pay attention to our limitations and our inevitable defeat. We are not only mortal, but we are aware of our mortality. From about the age of four years on, every child begins to understand that they and all those around them are destined to disappear. This awareness lends a mystery to our existence and leaves a taste in our mouths. The taste never fades, but it changes as it is imbued with different emotional meanings: we are here briefly, we meet each other with interest, we love deeply, and we experience acute loss.

Recognizing that we are finite and fallible is recognizing a deep truth of reality. However we use this truth — whether we become scientists who discover the limitation of human perception or we become spiritual seekers who try to make sense of our feeling for infinity in the midst of our impermanence — we gain wisdom from the knowledge of our limitations. We see that this wisdom is different from mere information or facts. My grandson was having a moment of wisdom on the couch.

He knew that finding the right pieces of the jigsaw puzzle was not exactly what we were doing; we were in a process of figuring out something that included making mistakes. Bob Dylan says in Love Minus Zero/No Limit, “there’s no success like failure and failure’s no success at all” and my grandson was contemplating the limits of success, what it does and doesn’t do for us.

AI Optimizes Success

I want to say something here about Artificial Intelligence in relation to Hoffman’s theory of survival fitness. Bear with me. When I first understood the idea of algorithms as they work in data mining and AI, extracting useful information by recognizing patterns in large data sets, I saw something I had not previously seen. It was a bit like my grandson’s insight about mistakes. I saw how AI works on winning — building success on successes. It does not recognize useful information in its mistakes or defeats.

Data mining in AI, especially in machine learning, is often about optimizing performance on a task. Algorithms are trained to identify patterns that help them achieve their goals like classifying images, generating text, and predicting outcomes. The training reflects what works — what is successful or optimal — according to correlations with the present data or information. Isn’t that similar to what Hoffman is saying in his theory of human perception?

Yes, there is a strong parallel between AI and Hoffman’s theory of perception. AI data mining shapes models to favor predictive power, not necessarily understanding the truth of what is being modeled. The implications are pretty wild: our senses evolved to be a kind of “user interface” not a window into reality or objectivity. Now, AI — trained on human data — is learning only the same user interface and not reality or truth. There may be a reality under what AI learns, but it is not accessible.

Human beings, different from algorithms, can learn from their mistakes, failures and defeats because we are immersed in an emotional reality. Our limitations create hard stops on our desires and longings, but they also teach us about reality — our impermanence, our imperfection and our need for different in order to find the truth.

Donald Hoffman / David McNew for Quanta Magazine

The Value of Mistakes

Let me illustrate this insight with another story about the value of mistakes, told to me by my friend Joel Forrester who is a jazz musician and composer. He’s been my friend since we were in college together and he lives in France now, but mostly he lived in NYC throughout his adult life. Joel was a protégé of Thelonius Monk who taught him by listening to Joel play and then making sideways comments about his playing.

Joel told me that when Monk initially listened to him for a few hours Monk said, “I don’t think you can become a performer because you don’t make enough mistakes.” When Joel asked what he meant, Monk said that in order to play in front of an audience, Joel would have to be inside the music enough to make mistakes and respond to them. In other words, Monk was telling Joel not to perfect his playing but to humanize it. He should become immersed in his experience and then make mistakes creatively. As he did this, Joel’s musical abilities deepened and came from a source that was not based in optimizing success. Monk’s approach contrasts with AI algorithms for extracting useful information.

Thelonious Monk at Minton's Playhouse, New York, 1947 / William P. Gottlieb

Real Dialogue: Finding Truth through Being Human and Making Mistakes

Real Dialogue exploits being human and making mistakes. It is both a mindfulness skill and a facilitation method for engaging with each other during conflict. Real Dialogue is not debate. There is no winning or losing or making a case or argument.

The aim is to speak authentically and listen responsibly, taking into account the limits of subjectivity. Instead of “making a case” for our arguments, we are “making sense” of each other. The parameters of Real Dialogue assume that we all “make mistakes” about what we see, hear, and believe all the time. We gain both knowledge and wisdom by being able to speak authentically about our disagreements because we see things through different lenses.

Human beings created AI to maximize success. As a tool, AI can bring great advantages for medicine, data analysis, composition, and graphic art, among other endeavors. Unfortunately, though, optimizing success can also bring a dehumanizing side effect: we may forget that we need to learn from our limitations and instead simply lean on optimal correlations with today’s information or findings. We may forget to face the truth of our limitations and begin to believe in our immortality or infallibility.

Because AI only knows how to win and doesn’t value defeat, it can readily become a tool for war (e.g. autonomous weapons) in which we falsely believe once again that “our side can success” while we create overwhelming loss for humanity. After decades of facilitating difficult conversations and witnessing the vast array of differences, perspectives, and insights from people in conflict, I am convinced that my grandson is right: we learn more from our mistakes than from our optimizing our successes.